Global food security faces major challenges, with 820 million people worldwide enduring chronic hunger that requires increased agricultural productivity and diversification of nutrient-dense crops1. Nearly half of the world’s calorie and protein intake depends on three staple crops: maize, wheat, and rice. Although around 12,650 plant species are edible, but people rely on only around 30 to meet 95% of global food needs, leaving most edible plants outside the main diet2. There are crop species characterized as having relatively low perceived economic importance or agricultural significance and receiving relatively little research, limited geographic distribution, low adoption, and no support from policymakers, technology providers, donors, and breeders that are termed as neglected and underutilized crop species (NUCS) or minor or orphan crops3,4,5. Once central to local diets and livelihoods, underutilized crops now receive little attention from agricultural research, plant breeders, and policymakers6,7. On the other hand, rice, maize, and wheat demand fertile land, irrigation, and intensive management, and receive higher priority from governments and researchers but are still remainhighly vulnerable to climate8. Stable crops, such as rice, wheat, and maize, provide primary caloric supplies with restrictive dietary diversity.

Underutilized crops grow well in marginal conditions with minimal inputs, adapt to diverse habitats, offer straightforward cultivation, store well, and carry unique nutritional benefits9. Underutilized crops are of essential value for food security and economic resilience in low and middle-income countries, especially mountainous and tropical regions rich in agrobiodiversity10. Millet, for example, grows mainly in Asia and Africa and shows the potential to strengthen nutrition, food security, and sustainable agriculture9. Nutritionally rich, drought-tolerant, and adaptable to challenging soils, millets are promising, but underutilized crops with the potential to improve food security and nutritional diversity11. In traditional diets, millets have historical importance, but modern agriculture has largely replaced them with a limited selection of staple crops12. Reintroducing these underutilized crops into our food systems can boost food security, improve nutrition, support income generation, and promote ecological sustainability13. However, challenges in supply chains, low consumer awareness, and the stigma of labelling these crops as “famine food” or “food for the poor” hinder their expansion14. Modern agricultural practices also have amplified these issues by reducing their diversity and removing them from the production system15,16.

Case of Nepal

Since the beginning of the 18th century or earlier, the indigenous communities of Nepal, such as the Newars, Majhis, Magars, and others, have had a long history of growing millet as a staple crop17. During the 18th century, there was a Malla dynasty in Kathmandu, where Khas people migrated from Kashmir through the Kumau and Garhwal regions of India, ultimately settling in Nepal’s hilly areas18. Historically, the Khas were agriculturalists known for their millet cultivation expertise and also introduced crops such as barley, wheat, and sesame19,20. In the Kathmandu Valley, fertile lands were dominated by Newar farmers who grew paddy, while unirrigated areas were farmed by Tamang and Magar communities cultivating millet and maize. The Khas settled in these (unirrigated) lands and continued millet farming. Over time, interactions between the Khas and local communities, such as those under Malla rule, led to agricultural practices and language exchanges. The Khas were eventually permitted to cultivate irrigated lands, further integrating their agricultural knowledge into the region18. The Khas contributed significantly to developing what is now the Nepali language (Khas Bhasa) and introduced their traditional farming techniques to the local communities. Over time, Khas people were integrated into Nepalese society and were categorized within the Hindu caste system, with many identifying as Chhetri and Brahmins (Bahun)20. Millets were a staple crop for upland areas with scarce water resources and were essential for food security and nutrition in the region. During the early 19th century, rural people cultivated wheat and rice to pay taxes while subsisting on barley, maize, millet, and supplemented by fruits and herbs19. Also, they used millet, such as kodo, sama, and kaguno, exclusively to pay tax to the local government, highlighting the significance of millet as a subsistence crop focused on revenue generation20. The semi-nomadic Khamba tribes, who lived in Karnali, Seti, Rapti, and Bheri during the mid-20th century, also relied heavily on millet cultivation. They cultivated millet, buckwheat, kaguno, and marse, which sustained their semi-nomadic lifestyles and livelihoods20. Mongolian groups in the Himalayan region have relied on wild plants and hunting since prehistoric times18. Over time, they transitioned to farming, cultivating crops like millet, maize, and mustard, particularly in the hilly terrains where rice cultivation was challenging. This adaptation laid the foundation for millet as a staple crop in the Himalayan agricultural landscape. Similarly, during the early 20th century, indigenous communities such as the Majhis and the Thamis were deeply intertwined with millet cultivation and its cultural significance18. The Majhis, who lived along the Sunkoshi and Tamakoshi riverbanks, relied on millet alongside maize and paddy as a key crop20. Millet featured prominently in their rituals and festivals, including the Aitabare festival, where millet flour was used to make baabar bread, symbolizing blessings and prosperity21. Millet liquor “rakshi” also played a central role in their festive and spiritual practices. Thami community, predominantly settled in eastern Nepal’s Dolakha district, cultivated millet extensively on rainfed lands. Traditional millet varieties like “dallo mudke kodo,” “chyalthye kodo,” “juwain kodo,” and “sunkoshi kodo” were vital to their agricultural repertoire22. Post-harvest, millet was processed using tools like the “gyalbi” for de-husking, and grain was considered an essential food source, especially during rice scarcity. Nutritious and energizing millet-based foods such as dhedo and roti sustained the Thamis throughout the year22.

The price of food grain in Jumla in 1779 at a unit “Paathi” current market price for rice, kodo, and chino, kaguno is Rs. 1665, 585 and 1800, respectively. The dollar conversion is $ 1 = Rs 13621.

Figure 1 illustrates the traditional Nepali unit of volume, Paathi, commonly used to measure grains. One Paathi is approximately 4.5 kilograms, providing a standard for analyzing historical grain prices in Jumla during 177921. Rice was priced at 8 rupees per Paathi, making it relatively affordable compared to other grains. This accessibility suggests its widespread cultivation and availability in the region. Conversely, millet (kodo) was priced at 12 rupees per Paathi, indicating a higher cost. The elevated price of millet might reflect its nutritional value, cultural importance, or limited availability compared to rice. Barley, at 16 rupees per Paathi, was the most expensive grain listed. The higher cost of barley may have stemmed from its dual use as a staple food, its potential demand for brewing purposes, and its possible scarcity in the region. These price variations highlight the economic and cultural factors influencing grain valuation in 18th-century Jumla, emphasizing the relation between agricultural production, dietary preferences, and market dynamics20. Millets have played a significant socio-economic role in Nepalese agrarian society, extending beyond their function as a food crop to serving as an economic instrument in historical contexts. Millet was often used as a form of payment for taxes and wages, particularly in rural areas where monetary systems were less established. Its value in barter transactions highlights its importance in sustaining local economies. Historical records suggest that millet’s resilience to adverse growing conditions made it indispensable during crop failure, providing a community safety net.

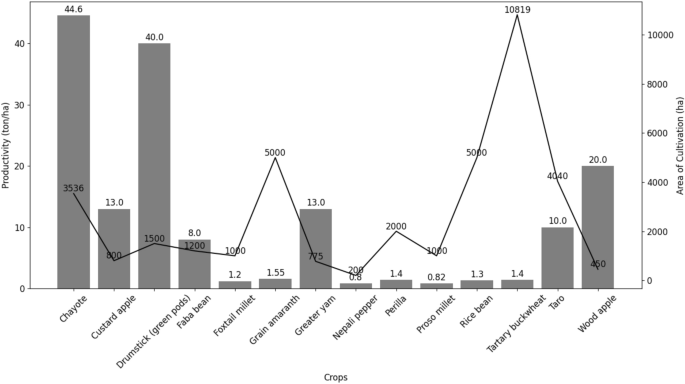

Nepal is recognized for its rich biodiversity that is a testament to its wide range of plant species. The country possesses 577 cultivated species as major crops, while 484 species are indigenous and are found in a different region23,24. The rich biodiversity of Nepal comes from it’s varied agroecological zones, ranging from the lowland Tarai to the high Himalayan regions, each supporting and suitable for different types of crops. Nepal is also one major country that is home to several neglected and underutilized crops (NUCs), such as proso millet (chino), foxtail millet (kaguno), sorghum (junelo), red amaranth (laal saag), wild millet (baale banso), wild rice (jungali dhaan), wild asparagus (ban kurilo), taro (pidalu, karkalo), yam (ban tarul), drumstick (sital chini), tartary buckwheat (titephapar), custard apple (sita fal), pokeberry (jaringo), wild fern (niuro), singing nettle (sisnu), ivy gourd (kundruk), etc24,25. These NUCs are known for their high adaptability to changing climates, ability to grow in marginal soils, and nutritional richness, making them valuable for food and nutrition security in Nepal. NUCs currently contribute a small portion to the overall food basket in Nepal, and they are cultivated on a relatively small scale compared to major crops such as rice, wheat, and maize. The productivity of these crops varies, such that foxtail millet yields 0.99 tons per hectare, proso millet 0.819 tons per hectare, and red amaranth 1.55 tons per hectare. In contrast, other NUCs, such as taro and yam, have higher productivity, at 10 and 13 tons per hectare, respectively24,26,27. Figure 2 shows information on productivity given by the right side of the y-axis and the cultivation area of various NUCs demonstrated by the line graph on the left side of the y-axis. The productivity is mostly higher than 1 for most of NUCs. These crops receive minimal attention in improving their yield, resilience, and adaptability to changing environmental conditions. Many underutilized crops produce smaller harvests and have poor shelf lives, reducing their appeal to large-scale production and trade. The underutilized crops are labor-intensive and market challenges also hinder the adoption of these crops. The rise of competitive crops, such as rice, wheat, and maize, which dominate agricultural markets and receive substantial research and policy support, squeezes these crops out of market niches, further neglecting these underutilized crops. NUCs suffer social, economic, environmental, agronomic and political challenges.

Productivity and area under cultivation for NUCS Crops y-axis right (Source: Ministry Of Agriculture and Livestock Development, 2017/18, 2021/22).

Neglected and underutilized crops (NUCs) are crucial in promoting sustainability, ecological diversification, economic empowerment of rural communities, and enhancing nutritional and health security28. Recently, there has been a growing global interest in rediscovering traditional nutrient-rich food sources29. Among these, millet stands out as a promising solution, offering both nutritional and agricultural benefits, particularly in addressing the challenges of food production under the pressures of climate change. Also, for Nepal, millet is an important crop after rice, wheat, and maize in terms of production area and food security. The millet cultivation spans a remarkable altitude range of approximately 60m to 3600m above sea level and contributes 1. 19% to the Gross Domestic Product of Agriculture (AGDP)17,30,31. In Nepal, approximately 39. 7% (58,512.71 \(km^2\)) of land area is suitable and has a high potential for millet31,32,33. Nepal’s agroecological zones also support the diversity of millets and exhibit a wide distribution across Nepal, growing in all 77 districts of the country30,34. The country has 12 domesticated millet species, such as (bristly foxtail millet, browntop millet, finger millet, foxtail millet, Japanese barnyard millet, job’s tear millet, kodo millet, little millet, Nepalese barnyard millet, pearl millet, proso millet, sorghum), they are all resistant to cold and drought conditions26,27,32.

Table 1 compares the nutritional content of various millet types with rice and wheat. It demonstrates that millet varieties such as pearl millet, foxtail millet, and proso millet exhibit higher protein and fat content than rice and wheat. For example, foxtail millet contains 12.3g of protein and 4.3g of fat per 100g, while rice has 6.8g of protein and 0.5g of fat. This comparison highlights the superior nutritional profile of millets, establishing them as valuable sources of essential nutrients. Similarly, Table 2 provides a comprehensive overview of millet production across different regions of Nepal based on data from the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development (MOALD) for 2016/1731. Millets demonstrate a wide array of health benefits and possess a rich nutritional profile, making them a valuable addition to dietary practices across the globe35. These grains are abundant in essential nutrients, including carbohydrates, proteins, dietary fiber, vitamins, and minerals34. Millets are exceptionally high in magnesium, phosphorus, manganese, and iron, nutrients that play critical roles in various physiological functions, including energy production, bone health, and oxygen transport. Moreover, millets represent a significant source of essential amino acids, making them especially advantageous for individuals adhering to vegetarian or vegan diets. These amino acids are instrumental for muscle repair, growth, and overall physiological well-being. Millets’ low glycemic index (GI) facilitates a gradual release of glucose into the bloodstream, providing a sustained energy supply. This characteristic renders millet a favorable option for individuals managing diabetes or those aiming to effectively regulate their blood sugar levels36. Rich in dietary fiber, millets promote digestive health by preventing constipation and regulating blood cholesterol levels. This fiber content contributes to enhanced satiety, aiding in weight management and control37. Being naturally gluten-free, millets are excellent alternatives to gluten-containing grains such as wheat, barley, and rye, making them suitable for individuals diagnosed with celiac disease or gluten sensitivity. Certain varieties of millet, particularly finger millet (ragi), are rich in antioxidants, including polyphenols and flavonoids38. These antioxidants are beneficial in mitigating oxidative stress and reducing cellular damage caused by free radicals. These antioxidants may also play a role in decreasing the risk of chronic diseases and associated inflammatory processes. Combining high fiber content and heart-healthy fats in millet supports cardiovascular health by lowering cholesterol levels, reducing blood pressure, and minimizing the risk of heart disease and stroke. Owing to their low caloric density, high fiber content, and ability to promote feelings of fullness, millets are advantageous for weight loss and management. Incorporating millets into dietary regimens can facilitate prolonged satiety, assisting individuals in achieving their health objectives37. Overall, millets emerge as a nutritious and versatile food choice that can enhance overall health and well-being. Integrating various millet types into daily meals can promote diverse nutrient intake and support a balanced, health-conscious dietary pattern.

A notable feature of finger millet, proso millet, and foxtail millet is their classification as C4 crops: plants that use a specialized C4 photosynthetic pathway39. This pathway allows C4 crops to capture carbon dioxide efficiently by forming a four-carbon molecule during the initial carbon fixation stage. This trait enhances productivity in hot and dry environments with intense sunlight26,39. This adaptation helps them conserve water and use nitrogen effectively, allowing them to thrive in low-fertility soils and under drought conditions where other crops could fail. Their resilience makes these C4 crops especially suited to the Himalayan foothills, offering a sustainable, climate-resilient option for agriculture in marginal areas17. In Nepalese districts like Humla, Mugu, Mustang, and Manang, these “Himalayan superfoods” rank as primary or secondary staples, serving as essential local food and nutrition security sources amid high poverty levels31. This positions millet as vital contributors to sustainable food systems and climate adaptation strategies in regions vulnerable to climate change17,30,

Millets are deeply embedded in Nepal’s cultural and culinary traditions, serving as a vital link between food and cultural diversity and identity21. Festivals and rituals across ethnic communities prominently feature millet-based foods and beverages. It is a key ingredient in traditional beverages like jand, rakshi, and tumba, which hold cultural and ceremonial significance21. The southern plains of Nepal, known as the Tarai, are well-suited for cultivating rice and transporting it to the hills and mountains, facilitating a vital exchange of agricultural products across ecological zones17. The tradition of the Tharu community to consume finger millet bread highlights the potential of fostering the interchange of crops and culinary practices between different regions and ecological niches30. Women play a pivotal role in preserving and diversifying millet-based culinary traditions. These include nutritious staples such as dhedo (a thick porridge), roti (flatbread), and festival-specific items like millet-based sweets and snacks. In addition, women contribute to food innovation by incorporating millet into modern products like noodles, papad, and bakery goods, ensuring its relevance in contemporary diets40. However, millet consumption in Nepal has declined as preferences shift towards rice, wheat, and maize, especially among younger generations who are less familiar with millet. This shift is due to urban migration and changing dietary habits. Despite their resilience and nutritional benefits, millets are often neglected in Nepalese agriculture due to low productivity, limited product diversification, and lack of awareness among producers and consumers. Millets can also offer economic opportunities by selling processed products, including “rakshi,” a traditional alcoholic beverage with crucial cultural value. Ecologically, millet supports environmental sustainability by promoting beneficial insects and improving soil health. These crops are integral to the country’s heritage, ecology, and environment, embodying a connection to tradition and livelihoods across Nepal.

Millet has untapped potential to increase food security, nutrition, health, and income, especially in the challenging agricultural environments of Nepal but formal research, education, and development programs largely overlook this crop23,27,34,41. Soil fertility is low in hilly and mountainous areas, and limited rainfall restricts farming options; however, millet can thrive in these conditions. As Nepal’s fourth most important crop after rice, maize, and wheat, millet is critical in mountainous areas with limited arable land and frequent food shortages41. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), UNICEF and the World Bank have created a database to calculate the Global Hunger Index (GHI), which measures hunger severity by combining data on undernutrition, child waste, child stunting and child mortality. The indicator is weighted and combined into a single score on a 100-point scale, where low hunger is 0-9.9, moderate hunger is 10-19.9, serious hunger is 20-39.9, alarming hunger is 35-49.9, and extremely alarming hunger is 50 or more, where Nepal score 19.1, placing it in the “moderate” hunger category42. With this moderately high level of hunger, Nepal urgently needs to diversify and strengthen its local food systems to improve food access and resilience. Population growth and increasing food demand add further pressure, with projected edible cereal requirements expected to reach 8.854 million metric tons by 2030, 10.07 million metric tons by 2040, and 11.46 million metric tons by 2050. The achievement of these targets will depend on the maintenance of productivity levels of 3.10 tons per hectare and an annual agricultural growth rate of 2.26%, with a population growth rate of 1.3% per year estimate26. Given these demands, millet’s ability to thrive in the Himalayan hilly and mountainous regions could be vital to ensuring Nepal’s food and nutritional security. Nepal can address the critical food demand and strengthen regional and national food security in the years ahead, focusing on the potential of millet.

Past studies highlight the critical role of fertilizers in millet cultivation, influenced by agricultural practices, socio-economic conditions, and the necessity of nitrogen fertilizers43. Hayashi et al.44 demonstrated that micro-dosing with fertilizer increases millet yields regardless of application timing. Eyshi Rezaei et al.45 found that using crop wastes and mineral fertilizer enhances pearl millet production more effectively than using either of the inputs alone. Sharma46 emphasized that combining fertilizers with farmyard manure positively impacts harvesting sequences and soil quality for millet production. Several studies have examined millet’s response to climate change, such that Bewket47 confirmed rainfall variability significantly affects cereal production, including millet, in Ethiopia. Maharjan48 noted that intense, concentrated rainfall severely impacts crop productivity, but off-season experiments showed that cowpea and pearl millet thrive under intense heat. Nelson et al.49 identified pearl millet as particularly climate-resilient and suitable for semi-arid regions due to its high tolerance for heat and scarce water conditions. Luitel et al.32 observed that rising temperatures, growing degree days (GDD), and decreased rainfall positively impacted finger millet production in central Nepal. Conversely, Karim et al.50 found that millet and sorghum remained resilient to climate changes in Ghana. However, Hossain et al.10 cautioned that early rainfalls and high temperatures during crop maturity could reduce millet yields.

Socioeconomic factors significantly influence millet production. Gitu et al.51 found that characteristics of household heads, cultivation area, cultural factors, technological qualities of millet varieties, and agricultural knowledge positively affected finger millet production in Kenya51. Handschuch and Wollni52 analyzed data from 270 households, discovering that modern seeds and fertilizers are more common in maize production than finger millet. They also found that social networks and access to extension services play a crucial role in adopting improved finger millet practices, while these factors are less significant for maize cultivation. Mukhtar et al.53 showed that socioeconomic factors such as cooperative participation, debt, education, extension contact, family size, and off-farm incomes positively affected pearl millet production in Nigeria53. Population growth, increasing food prices, and urbanization present major threats to millet cultivation, especially for low-income individuals in the Asia-Pacific region12. Millet production remains popular in rural areas due to its low water requirements. However, rapid urbanization alters food accessibility and sustenance means, shifting economies from agriculture-based to alternative income sources54,55. However, Bhatt et al. (2023) highlighted the increasing urban demand for millet flour, noting its potential health benefits for diabetes, cardiovascular issues, obesity, skin conditions, cancer, and celiac disease56. Ma et al.57 and Lubadde et al.58 emphasized the role of cultivated areas in increasing millet production. However, Gebreyohannes et al.59 found a negative relationship between cultivated area and millet production. Saxena et al.11 reviewed studies showing a decline in millet production areas due to governmental support for key grains like rice and wheat. They highlighted the environmental benefits of cultivating millet over major cereals, suggesting a shift to mitigate food insecurity and environmental stress in regions most impacted by climate change. Millet cultivation has declined due to government support for other grains, but millet’s environmental benefits can help address food insecurity and climate challenges.

Despite extensive research on factors affecting millet production, there is a gap in studies focusing on millet’s climate resilience. Most research emphasizes production determinants without thoroughly investigating millet’s role in ensuring food security amid climate change. This study aims to fill this gap by examining millet’s climate resilience using Nepal as a case study from 1980 onwards. It will provide insights into how underutilized crops like millet can enhance food security and adapt to climate challenges, offering valuable data for policymakers and agricultural stakeholders. This study analyzes millet production dynamics in Nepal, emphasizing the broader benefits of millet beyond production determinants. It contributes to the literature in two ways: first, by being the first study on millet production in Nepal using time series data; second, by providing insights into how Nepal’s climate influences millet production. It also includes a trend analysis of millet compared with major crops like rice, wheat, maize, and barley.